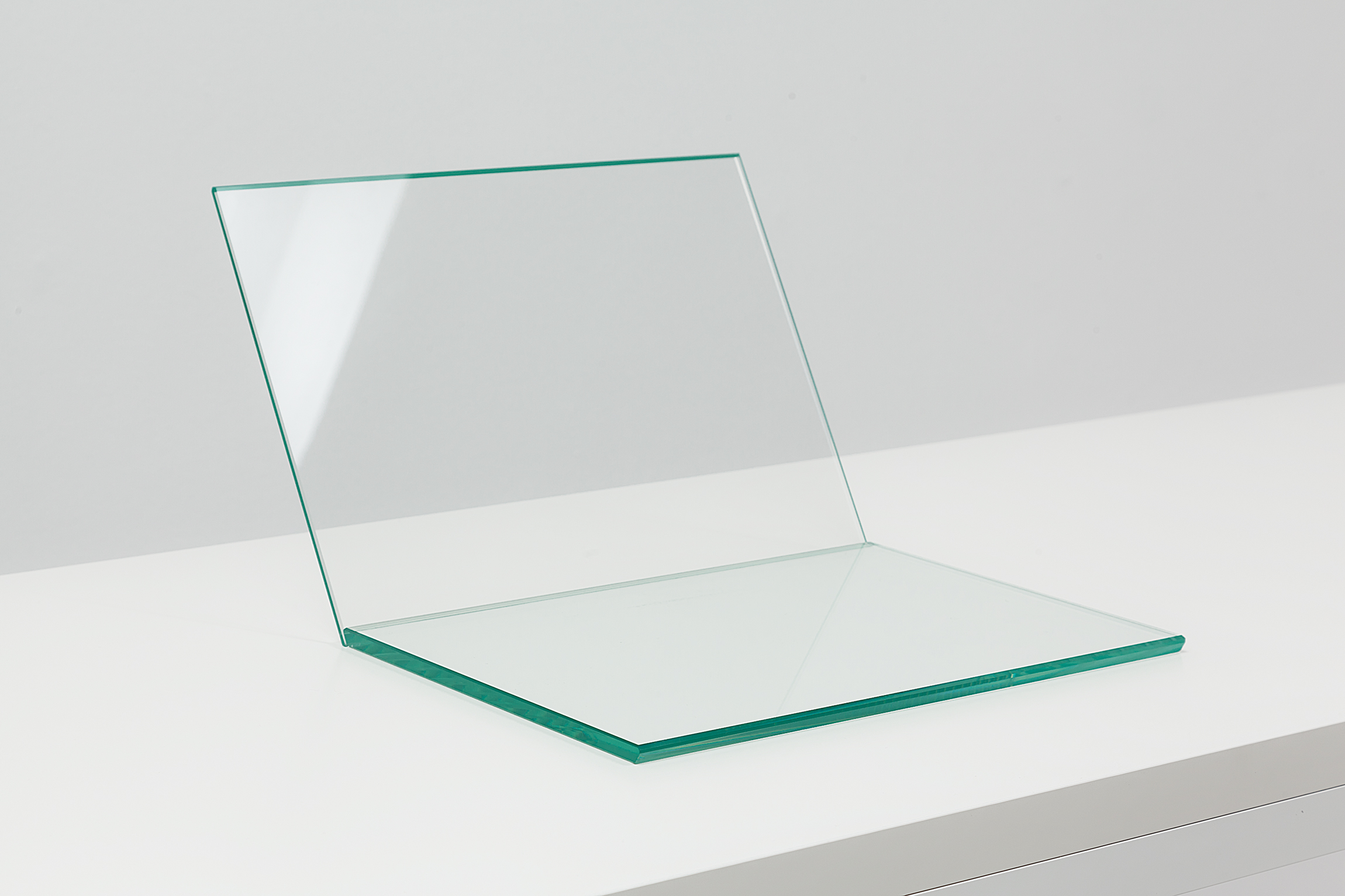

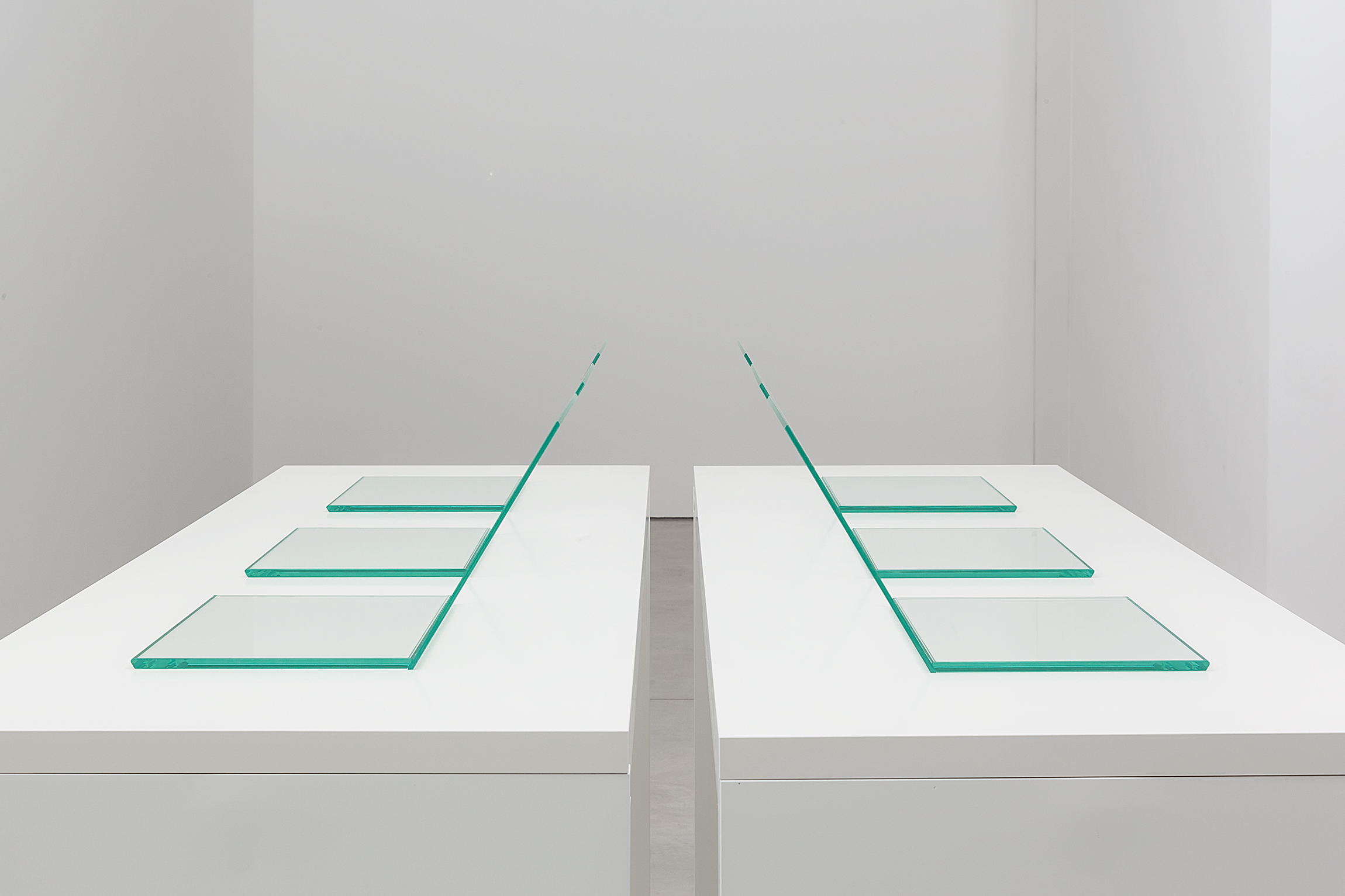

GlassBook - Content is King!

Tilman Hornig - GlassBooks in sizes 11", 13", 15"

Content is King! - Galerie Gebr. Lehman, Berlin, 2014

Exhibition Text

The Diaphane:

On Materiality and Immateriality of the Computer Screen

“Limits of the diaphane. But he adds: in bodies.

Then he was aware of them bodies before of them coloured. How? By knocking his sconce against them, sure.”

James Joyce: Ulysses

Metaphors flourish where the overwhelmingness of the sublime is in danger of condemning us to speechlessness – when we are con- fronted with the existential quaternary of death, god, nature, and love. Today, nothing is described by so many metaphors as the com- puter. According to Apple’s Steve Jobs, it is a “bicycle for the mind.” Microsoft’s Bill Gates describes the computer in more sober terms as “a tool.” The neurologist Peter Whybrow, in turn, warns hysterically that the computer produces actual cascades in the brain’s reward center, just like “electronic cocaine.”

Concerning its revolutionary impact on social structures, it is com- monplace to compare the computer to the “printing press.” Since the sixties, more comprehensible, but generally contradictory images are in use, including “super calculator,” “great library,” “toy,” “type- writer,” “notepad,” and the anthropomorphizing “assistant.”

As a consequence of our speechlessness in the face of the techno- logical sublime, we are looking at the computer as a mirror that should reflect ourselves. For a long time, we’ve used the metaphor of the computer being a “brain,” which ultimately went so far that the human brain, in turn, has been described in terms of a computer, instead of the other way round. Alluding to the Turing Test defining artificial intelligence, informatics pioneer Joseph Weizenbaum dub- bed the computer a “human pretender.” Fittingly, the computer “runs” in our contemporary imagination or – most often tragic – it “dies.”

Strictly speaking, because of their enormous flexibility, computers are indescribable. Their level of being is not the same as that of any other object, but rather that of a transcendental apparatus, through which every possible perception must pass in order to be real. Similar to the Kantian “green glasses” that dye all of reality green – an image employed by Heinrich von Kleist who met despair because of Kantian transcendental philosophy – the computer screen today is a prism, through which the light of reality reaches us, and which dyes that reality according to its structure, in accordance with the specific permeability of its crystals.

Only the computers of banks and stock markets materialize property. Only the digital archiving and normalization of social relations on microchips produce stable, continuous contacts. Only the recording and comparing of our data by medical computers make it possible to speak of health. In some countries, computers are already calculat- ing the results of elections by themselves. Because of their indis- pensability to modern physics, computers also define what we con- sider to be real. At this point, one has to correct philosopher Quentin Meillassoux, among the most ardent of Realism’s contemporary defenders: real isn’t what can be expressed in formulae. De facto real is what can be calculated by computers. Where computers fail, the horizon of our binding reality also ends – everything beyond that is “merely subjective.”

From an ontological point of view, computers – similar to Heidegger’s notion on Being – “are” not at all. Today, they are required to deter- mine any kind of being. They, therefore, precede any kind of being. Computers “are” not, they exist as an invisible given, which pene- trates everything. Foremost, computers are nothing specific. As a universal medium, they are similar to that which Aristotle called the diaphanes, the “transparent” – an undetermined “in-between,” metaxu, which has to be formless in exactitude to take on any form and to transport all possible impressions. The significance of the computer also correlates to an image of the Stoics, the apeiron, ”the in-finite,” which, being primal matter par excellence, includes the possibility of any other matter, and which, exactly because of that, has no proper qualities itself.

It is therefore no accident that transparency is the ethos of our time.

The absolute permeability of the computer has evolved into a meas- ure for the organization of human relations and politics. In the face of the total permeability of the digital-diaphane primal matter, all infor- mation is equally decontextualized and deformed, transformed into mere “content” on the internet. And being the result of this process, the “content” we find on the internet does not contain anything, but is similarly deformed, in a subliminal way as empty as the computer itself.

Consequently, metaphors are also running wild when attempting to describe the internet. Being speechless in a proper sense, misnomer is added to misnomer. In one instance, the net is pastorally described as a “global village,” in another instance antithetically as a “highway,” and even more hysterically as an “ocean” or a “jungle” from which we have to “protect our children.” Or is it, after all, only a “playground for brainless narcissists”? To the net theorist Kevin Kelly, it is “a copy machine.” Orville Schell, a professor of journalism, said the computer was “like radioactivity,” because “once released, it is nearly impossible to contain.” From a political perspective, it was first claimed that the internet was like “oxygen to dissidents.” After the unveiling of the inner workings of the digital-military complex, which connects Microsoft, Google, Apple, Facebook, and several secret services, the internet was suddenly regarded as “the wet dream of the Stasi.”

First of all, “content” doesn’t contain anything in the proper sense, because this would require a purpose, a motive of the information on the internet that superseded the mere form, the medium. Without such context, there is no content in the proper sense. And the computer knows only one context: itself. Therefore, the majority of the information that we receive via the internet deals with the appara- tus itself. How fast is the new iPhone? Or, is Samsung better after all? By which new functions is Facebook violating our private sphere in an even more menacing way? In which software-firms should one invest today and which stocks should one sell right before the inevitable collapse of the next tech-bubble? What will change when private 3D-printers in children's rooms produce firearms? McLuhan’s formula, that the medium is the message, was never truer, never more absolute. The “content” of the internet is the nothingness of the computer and nothing more.

What is, paradoxically, most necessary in this world, is to forget about the computer itself, because otherwise everything would seem terribly one-dimensional and wan. Although we constantly talk about the computer and by means of the computer, we never talk of the computer in the proper sense. It is easier to believe we are looking at different things, when in fact we are just staring over and over at the same screen. The wall of metaphors which surround the computer bare witness to our essential silence in regard to the computer.

If there is an assertion, a meta-narrative at all, which does justice to this silence, it is the assertion of the immateriality of the computer. John Perry Barlow wrote in his “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” of 1996: “Your legal concepts of property, expression, identity, movement, and context do not apply to us. They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here.”

Barlow’s text was frequently ridiculed, but today it is fundamental to the political demands of the digital elite. The immateriality of the computer that is stated in this declaration became the foundation of the promise that – by its mere existence – the computer would trig- ger revolutions in virtually any material sector – politics, law, economy – as if it was an intervention by a deus ex machina from a better, pristine world before the fall from grace into earthly matter.

In the new Californian techno-gnosis, a Manichaean division is predominant, a division between the analog, demiurgic world of the “weary giants of flesh and steel” and the immaterial, light-flooded world of the “new home of mind,” which the computer pretends to be – both expressions stem from Barlow’s “Declaration of the Inde- pendence of Cyberspace.” A richer culture of “sharing,” direct democ- racy, the emancipation of women and consumers, breathtaking solutions for societal and environmental problems – all this shall happen practically automatically, once the fiber-wired portals to the im- materiality of cyberspace gape everywhere within the material sphere, once every single brain is transformed into a portal to the hive mind.

In regard to the phenomenology of the object, looking at its surface from the outside, one can already recognize the desire of the com- puter to negate its materiality. In no other sector, the tendencies of technology and design towards their own vanishing are so clear. According to Moore ́s Law, the capacity of microchips doubles every 18 months. A true obsession to minimize everything reigns, which has already compressed the capacity of the room-sized machines of the fifties into the size of a pants pocket. Once, the human brain was the most complex structure of nature. Today, it is the microchip. As if they wanted to amplify this ever and ever more spectacular disap- pearance of matter, the screens of laptops and smartphones are getting larger and larger. To gaze into an abyss of nothingness from a box seat, in colors as brilliant as the sun: this is the dream of our age.

Immateriality, which the computer states so vehemently with all of its existence, is its most cunning trick. Immateriality seems to discon- nect the computer from the whole world, from the corrupt structures of law, economy, and power of the material realm, to which it is in fact entangled. The proper question – the blind spot of the discourse of the computer – is the question of the materiality of the computer.

The illusion of the immateriality of the computer brought along hopes for better, more ethical industries and politics, which wouldn’t be based on the destruction of the environment via wars for raw materi- als and human exploitation. These hopes were a gigantic deception. Computing capacity requires power – at the moment roughly 10% of the energy globally produced – and it needs minerals, for the sake of which wars are being fought today in Congo and Afghanistan. The fairy tale of digital democracy was impossible without the cheap laptops and junk smartphones which tax avoiding American firms extract by the use of mental and physical violence from their Chinese working slaves.

The alleged “sharing” in social networks fills up the pockets of the new net monopolists and lets the archives of the state-run surveil- lance organisms swell to historically unprecedented extents.

Instead of a new golden age, we are witnesses to the dawning of cyber-totalitarianism, invulnerable as it remains without a face, without a form, without a space, without a body. The hopes for a bodiless information-economy turned out to be ideology in the Marxist sense, i.e. a “reversal of reality.” The consumer who is dwel- ling today in the exertive attempt to seem bodiless, characterizing the aesthetic of Apple and similar firms, dwells in a reversed reality, in which the screen must lose its materiality in order to disguise the fact that without it, everything would cease to exist.

by Johannes Thumfart, 2014